Before our short digression into the graffiti of Havana, we were just about to pull up to the Hotel Nacional de Cuba, right on the eastern edge of Vedado, a neighborhood that extends from the west side of Centro Habana to the Almendares River and southward down to the Plaza de la Revolucion (which we’ll visit in an upcoming post on May Day).

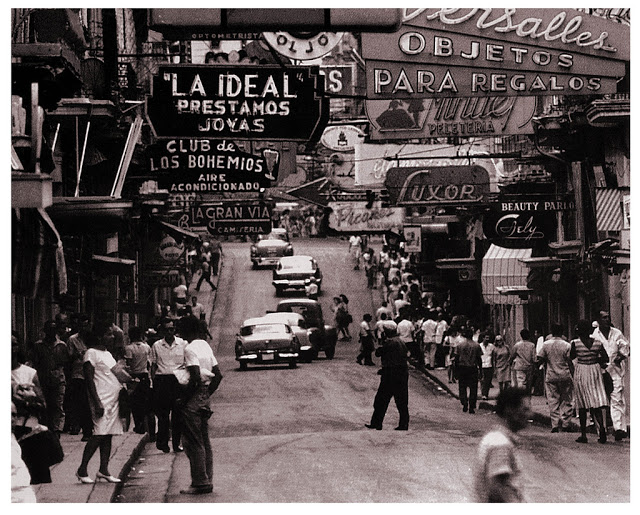

Looks like a ’50s film, no?

Vedado is quite a step up from Centro Habana. The houses are far better maintained, and it’s dotted with higher-end hotels and embassies (including the new US embassy). Even though I spent a good part of my free morning exploring the area around the Hotel Nacional and along La Rampa (aka Calle 23, the main street in Vedado), I didn’t get to see it all.

The Hotel Nacional alone was worth the drive across town. Standing high atop the former Santa Clara Battery (duly marked with cannons), the hotel opened in 1930 and was famously the site of the Havana Conference in 1946, when Lucky Luciano brought together the Mafia leaders of the United States and Cuba.

There’s a room named after Jean-Paul Sartre, who stayed there with Simone de Beauvoir in 1960, as well as a Winston Churchill bar. The hotel also appears in Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana (like so many other spots around town, as explored in this article from Atlas Obscura).

After sneaking around the Hotel Nacional for bit, I headed over to the Tryp Habana Libre (formerly the Havana Hilton). The lobby feels like a set for Mad Men.

While my group later drove past some of the famous casinos of the Batista era, unfortunately I did not get a chance to go inside or take pictures. I was fascinated to learn, though, that those American Mafia–run casinos were one of the first targets of the revolucionarios when they took Havana on January 1, 1959.

After a brief stop at a flea market in a vacant lot, where I made an regrettable decision about a straw hat, I continued up La Rampa to La Coppelia.* This is Havana’s famous “ice cream cathedral,” where locals and tourists alike go to enjoy a sundae. Since tourists use a separate currency from Cubans, there are different lines for foreigners and locals, but in both cases one pays by the weight of the ice cream.

*The opening scene of Fresa y chocolate, a well-known Cuban film about sexual politics under Castro, takes place at La Coppelia. The film was nominated for a Best Foreign Language Oscar, and it’s quite good—kind of a Cuban take on an Almodóvar movie.

Long ago, back in my post on Habana Vieja, I promised that we would find a Don Quixote to go along with the Sancho Panza statue on the Calle Obispo. Entonces mira:

I also wandered around the backstreets of Vedado searching for a synagogue. One of my workshop partners, Nancy, had asked about Jews in Cuba, and this sign was the only trace I saw of their presence on the island.

I followed the sign but never found the synagogue, and the people I asked looked at me like I had two heads.

Instead, I stumbled upon a neighborhood cafeteria where local workmen were stopping in to get lunch, which was doled out on aluminum trays. No one seemed to be paying for this food, so I asked the lady at the counter if I was allowed to eat there. She was perfectly willing to give me a free plate, but her manager soon emerged to explain that only locals could eat there.

So I walked back from the Hotel Nacional to the Plaza de San Francisco (a 4.2 km hike beneath the blazing sun), and I stopped for some paella and a cold beer along the way …

The video below was taken on a different day. Here, the Cuba Writers Program is taking Bus 5050 through Vedado to Marianao.

Marianao is another neighborhood I was eager to explore, as I had decided to use it as the location of Elena’s mother’s home in my novel The Crimes of Paris (“on Avenida 41, just across from the Cine Lido, a run-down movie house with a blank marquee and a colorful but faded geometrical design on the façade”). I didn’t get to see the Cine Lido, but the neighborhood conveniently conformed in reality to my fictive descriptions of it. (Sometimes we novelists get to give ourselves the rare pat on the back.)

We traveled all the out to Marianao to see the Habana Compás Dance company perform. Afterward, we headed to still another area called Diez de Octubre to visit a barrio that’s been transformed into public art by the Muraleando Artist Community. But you’ll have to wait for my next post to see those …